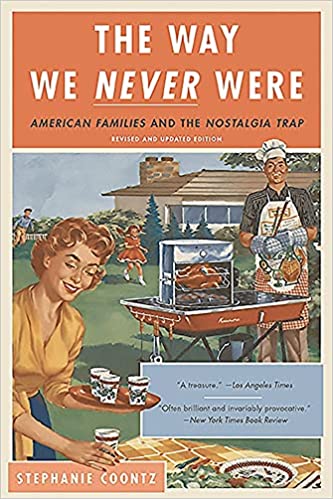

The Way We Never Were by Stephanie Coontz

The role of the family is a source of confusion in American life. Many people believe - explicitly or implicitly - that the past contained a golden age of family values (usually the 1950s) whose wisdom we have since forgotten. There is a political consensus that the institution of the family is dying, with the left blaming capitalism and the right blaming feminism. Most people self-identify as having “old-fashioned” values about families while also holding plenty of beliefs that are very novel.

The past was not a utopia and the present is not a dystopia. When viewed in historical context, many recent shifts in American families are less unprecedented, less unpredictable, and less dire than they first appear.

There is no such thing as a “traditional” American family. Family diversity is the norm in American history and not the exception. Even in the most homogeneous period in American history - the nuclear-family-oriented 1950s and 1960s - such families still represented less than half of all households. People from lower economic classes, racial minorities, and recent generations of immigrants have always had family structures that differed from the mainstream. Non-mainstream family types have rarely gotten much representation in mass media, often leading modern people to believe the past was more monolithic than it really was. When modern people are asked their definition of a “traditional” American family, they often list a hodgepodge of ideas from different time periods that never coexisted.

Confusion about family has deep roots. Most modern-day confusion about the role of the family originated during the industrial revolution. Industrialization formalized governance and much of the economy, empowering impersonal institutions at the expense of traditional social networks. Industrialization also led to a greater share of work being done outside of home rather than inside. The result was a sharper distinction between economic and non-economic work and between public and private life. People usually responded to this two-tiered life by doubling down on their immediate families and establishing them as the boundary between the two worlds. The family was to be a sacred sanctuary where the dog-eat-dog rules of the outside world did not apply. This definition of the family has been revisited and revised by every generation since.

Families have never been self-sufficient economic units. Industrialization created the idea that a society is a collection of distinct families, each of them economically independent. The idea of self-sufficient families is an idealistic dream that has never been realized in practice. People often look back on colonial frontier settlers and 1950s suburbanites as independent families who stood on their own two feet, usually not knowing that these were some of the most heavily government-subsidized people in history. Every generation has had a significant portion of the population living in lifelong poverty who needed outside help to survive. It has also always been common for well-off families to need outside aid from time to time in response to common economic or family shocks. Before the modern welfare system, such aid was usually handled by extended relatives, religious and civic groups, or local governments. Every generation has had a moral panic when the young generation appeared to have difficulty establishing complete economic detachment from their parents. The self-sufficiency myth is persistent in part because older people habitually exaggerate the extent to which they are self-made and independent.

Families have never had full autonomy and privacy. Many people believe that a man’s home was once his castle and that family business was once nobody else’s business. The opposite is true; before industrialization created a distinction between public and private life, there was almost no concept of family privacy at all. Extended relatives, neighbors, civic organizations, and local leaders regularly kept tabs on the people around them to make sure they were living their lives in a socially-conformant manner. These informal external stakeholders were willing to take drastic action against families they deemed unfit, up to and including separating children from their mothers. The modern system of family law is not a novel intrusion into family autonomy, but rather a formalization of processes that were once done in an ad hoc way.

Families are not the historical source of morality. Industrialization created the idea that morally healthy societies are created from the bottom up by morally healthy families. The disciplining and moral education of children had historically been done by a wide variety of stakeholders, including extended relatives, neighbors, churches, schoolteachers, and apprentice masters. Moral education increasingly got put into the hands of parents, who often taught children that their families were the only people they could truly trust and that they should always side with their families in the event of a conflict. Industrial societies accepted self-serving behavior that agrarian societies would have condemned outright, as long as that self-serving behavior was done in the name of one’s family. By sharpening the division between public and private life, industrialization sharpened the division between public and private morality. Since people’s closest relationships were with their immediate families, private family life was viewed as more revealing of a person’s true nature than public behavior. Only in the late 19th century did news media begin regularly disclosing the private family and sex lives of politicians and public figures. With family becoming so important, it started becoming viewed as the meaning of life and became a way for people to claim moral superiority over others. Anyone poorer than you was pathetic, while anyone richer than you was probably forgetting that family is ultimately more important than money.

Women have always been involved in public life. Women have long contributed to the finances of agrarian families by working for the farm and selling homemade goods. Industrialization created the idea that the public sphere belonged exclusively to men and the domestic sphere belonged exclusively to women; women formally lost some of the economic rights they had once held informally. This gender-segregated world was hardly a utopia; women resented their economic dependence and men resented their economic obligations. Spousal relationships in the 19th century were famously stilted and formal because men and women had trouble relating to each other’s very different lives. However, women’s participation in the labor force has been going up decade-over-decade since the 1880s, starting with the poorest families and increasingly extending to the affluent. The rise of female work was driven mainly by the industrial economy’s high demand for labor as well as new technology that made housewife work less time-consuming. In many ways, the 19th century was an anomaly and the confusing multi-dimensional lives of modern women are a return to historical norms.

People have never been good to the elderly. Modern adults deal with social flak and inner guilt when they put their elderly relatives into nursing homes. Modern adults often believe they are breaking an old tradition of family care for the elderly; however, this tradition largely doesn’t exist. The elderly have historically been a tiny percentage of the population and they have historically been the most impoverished segment of society. Elder care needs to be recognized as a novel problem that few societies have faced and no society has successfully solved.

People have never been sexually chaste. The limitation of sex to married couples is an idea that has long existed in theory but never in practice. In the 19th century, as many as one third of brides were already pregnant on their wedding day. 19th century cities had as many as one prostitute for every fifty men; prostitutes were the most common way urban men lost their virginity. Somewhere between 20-40% of pregnancies have always ended in abortion or infanticide, even when such acts were illegal. Teenage motherhood did indeed increase (and later fall) in the 20th century, but it wasn’t because of looser sexual morals. Due to poorer overall health, teenage girls have historically hit puberty at a later age than today; they were less likely to conceive successfully and more likely to miscarry.

The scope of parenthood has grown. Many socialization and child-rearing functions once done by extended relatives, neighbors, or hired help are now centralized in the hands of parents. Industrialization eroded the importance of extended kin, friends, and neighbors, leaving modern parents with smaller social support networks. Early 20th century parents therefore employed a low-effort parenting strategy; they avoided being too accommodating of their crying babies (they feared spoiling them) and had laissez-faire attitudes towards their older kids. Cultural expectations for the extent of parental involvement rose in the mid-20th century mainly due to media pressure, making parenting much more time-consuming than before. It became fashionable to blame all personal and societal problems on bad parenting. Parents started viewing themselves as the primary determinant of their children’s lives, leaving as little to chance as possible and then feeling guilty when their children didn’t turn out as hoped. The idea of the centrality of parents peaked around the 1950s and has since eroded in the direction of old historical norms. When women started working in increasing numbers and daycares became more common, social conservatives feared this would create a generation of insecure, anxious, and unattached people; this didn’t happen. When divorce and single parenthood started rising, social conservatives feared this would create a generation of psychopathic kids who have no concept of family duty and only care about themselves; this didn’t happen either.

The rise of divorce and single parenthood is not what it seems. The late 20th century had a huge moral panic about broken families and their effects on children. In the 19th century, as many as half of all children experienced the death of one or both biological parents before they turned 21. Broken nuclear families have always been common and there has never been a historical golden age of intact families. Divorce is correlated with poorer outcomes for children, but the same poor outcomes also occur for children from dysfunctional couples who stay together. No-fault divorce has enabled the breakup of countless abusive relationships that would have otherwise continued; people who initiate divorce rarely regret doing so. With individual people (especially women) being increasingly educated and increasingly able to support themselves economically, single parenthood has gone from being unthinkable to merely being difficult. In the long term, the strongest predictor of a child’s economic prospects is the education level of the parents, not the composition of the child’s household.

Economic circumstances drive family culture, not the other way around. Family structures have always been a response to the practical realities of their era. For example, the male breadwinner ethic intensified during industrialization because good fathers wanted to keep their wives and children out of sweatshop jobs if they could afford to. Fertility rates fell once children lost all their old economic value as child laborers and became economic burdens instead. Black American families continue to have a distinct agrarian character (eg complicated extended families, strong matriarch figures, low gender segregation of household work) because economic industrialization largely bypassed them. Household sizes were high during the early industrial era, then started falling in the mid-20th century once the housing supply increased. Women became more prevalent in workplaces starting in the 1880s because of economic reasons, not starting in the 1960s because of feminism. As women gained greater economic power, the dating scene became more egalitarian and many old sexual double standards favoring men started eroding. As mothers started increasing their share of economic work in two-income families, fathers compensated by spending more time on housework and childcare. As divorce became easier, more people than ever before are now getting married at some point in their lives. It has often been fashionable to blame social and economic problems on poor family morals, but this gets the causality backwards. Both in the past and in the present, most misery is ultimately caused by poverty.

Trends become popular first and socially acceptable later. Most family trends throughout history have occurred because of ordinary people living their lives and responding to their circumstances. There has always been a decades-long lag between what was normal in practice and what was considered normal in theory. For example, divorce rates started increasing in the mid 20th century, but divorce itself remained taboo until decades later. Homosexual couples started living more openly in the late 20th century, but public support for legally recognizing their relationships didn’t rise much until decades later. Working mothers were viewed as a negative social phenomenon for decades before they started being viewed favorably. Pre-marital sex, while always being common, finally lost most of its stigma in the late 20th century after the Baby Boomers started practicing it much more openly than past generations. History books overstate the power of activists and politicians in deciding the nature of the family. People have lived in a wide variety of family structures throughout history and young people will readily accept their world as being normal.

Homogeneity comes at a steep price. Cultures and governments have sometimes elevated a particular family structure as superior to others, but this preference inevitably comes bundled with an intolerance towards other family structures. Time periods where governments tried establishing family norms (eg late 19th century, mid 20th century) have usually also seen crackdowns on contraception, abortion, and various consensual sexual behaviors. The highly homogeneous 1950s suburbs were not an idyllic utopia, but rather a stifling and conformist culture that modern people would find unacceptable. In the 1950s, the marriage-house-children script was so pervasive that ambivalent people played along with it simply to avoid becoming social outcasts. Women who didn’t aspire to be supermoms and superwives were seen as defective and self-indulgent, while men who didn’t want to be solo breadwinners were viewed as childish and subversive. Social support networks were non-existent and all problems were viewed as the personal failings of the parents. There was a significant epidemic of alcoholism among women, almost always kept secret. Families went to great lengths to keep up appearances and to make sure nobody else knew about their internal problems. The modern era is much more diverse and tolerant; this is mostly a good thing. Modern people are not living according to a rigid and unsustainable life script but are individually customizing their life journeys. They are choosing different subsets of {higher education, career, independent residence, marriage, children}, completing these traditional adulthood milestones in different orders and at different ages. This is not a historical anomaly; the rigid 1950s-style life script was the anomaly.