Factors Affecting Code Change Frequency

March 2021 was a dubious milestone in my software engineering career: it was my first month where I did not merge any changes to any codebase. This happened on a month where I worked perfectly regular hours and took only one vacation day.

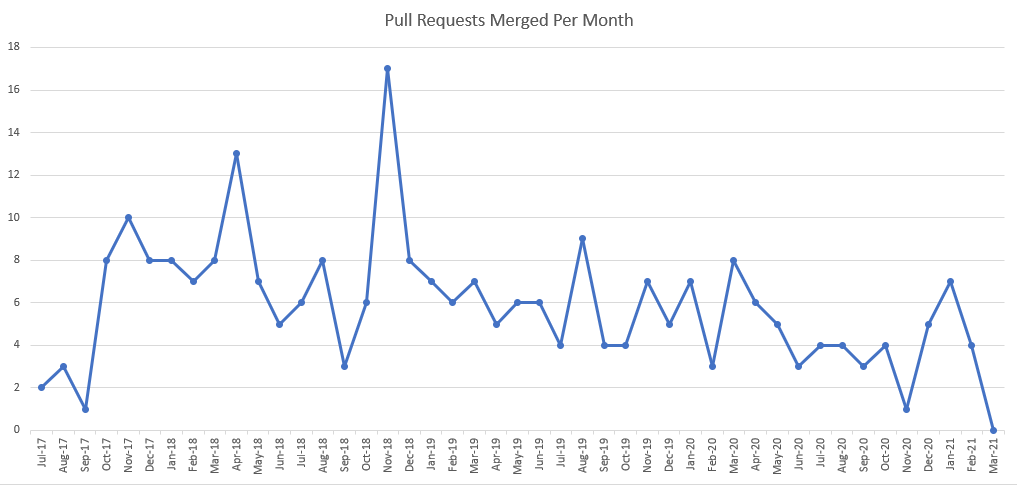

I have been tracking my pull request counts in my logbook since starting my current job about three and a half years ago. Bucketing all completed pull requests into the month in which they were merged, the result is this timechart. March 2021 is the first month where the count is zero.

The first trend to note is that my pull request counts at my current job are (and have always been) quite low. If high-school-age me saw these kinds of numbers, he would have wondered what I’m doing all day. Before Microsoft, I interned at Remind and averaged around 12 pull requests per month. Before Remind, I interned at Google and averaged around 6 changelists per month. Before Google, I interned at QuickTapSurvey, where I pushed code almost every day and where merging five or more pull requests in one day wasn’t all that rare. During my Microsoft tenure, I have had the chance to participate in some weekend hackathons for unrelated projects. At these hackathons, I would push five or more pull requests a day on a codebase I had never seen before, only to go back to my day job on Monday and return to pushing one pull request per week. Code change frequency clearly depends a lot on the project and not just on the developer.

The second trend to note is that even within my current job, my pull request count has been slowly declining over time. 2018 typically had around 8 PRs/month, 2019 averaged around 6 PRs/month, and 2020 averaged around 4 PRs/month. Even though my seniority and competence have both risen during this time period, the trend shows a noisy but gradual decline. The only major structural changes in my day job were a change of manager (July 2018) and an ongoing work-from-home stint that began in March 2020; neither occasion is marked with a lasting jolt in the graph.

So what gives? What factors cause code change frequency to be higher or lower? Based on my experiences, here are the most important structural factors.

Position on the stack. In general, the higher a module is on the stack, the more commonly it gets changed. The presentation layer changes a lot, the business logic layer changes less often, and the infra layer rarely changes at all. Low-level code is by definition likely to be mature and stable, given that developers are comfortable building new code on top of it. Maintainers of low-level code often have their hands tied because of the need to support pre-existing contracts; they often can’t change code even if they want to. The process of testing also gets slower with stack position; UI changes can often be verified just by eyeballing them, logic layer changes usually require writing unit tests, and infra-layer changes often require slow integration-level testing.

Codebase size and complexity. In general, the bigger and more complex a codebase is, the more rare and more difficult it is to change it. As much as everyone tries to keep software clean and modular, larger codebases inevitably have more coupling, more layers, and more technical debt. Doing a code change on a bigger codebase requires more reading, more thinking, and more testing. It takes a longer time for developers on a large codebase to ramp up and become productive coders; notice how my PR count was very low until my 4th month.

Non-production vs production software. In general, customer-facing software is built under higher engineering standards than internal-facing software. Likewise, software that is already in production is subject to higher standards than in-progress software that hasn’t yet been released. Non-production software is more likely to be missing quality controls, more likely to have lots of bugs and UI problems, more likely to have been built up on a piecemeal basis, and more likely to have a constantly-evolving purpose; all of these factors lead to frequent small-scale code changes. Just before a non-production piece of software transitions into a production piece of software, there is usually a burst of coding activity as long-standing quality problems are addressed. The highest two points on my timechart are examples of months just before pre-production software became production software.

The software’s release cycle. In general, software teams with fixed periodic release cycles have more code changes than teams with continuous release cycles. Before a periodic release, there is usually a coding scramble as pre-release testing is done and many quality problems get reported all at once. On teams where releases are frequent and the main branch is expected to be production-worthy at all times, the time pressure to ship a feature is lower, there is a higher stigma against pushing low-quality or partially-finished code, and quality problems get fixed on a smoother and less bursty schedule. For better and for worse, teams with a “move fast and break things” culture do more iterations than teams with a “get it right the first time” culture.

The hassle of opening a pull request. The pull request process is more frustrating if the pre-checkin test suites take a long time to run, if the pre-checkin test suites are flaky, if code reviewers have a slow response time, if code reviewers are nitpicky, or if the rules regarding code review approval are demanding. If the process of pushing code is a major hassle, developers are more likely to make a smaller number of larger pull requests.

Task distribution by seniority level. Any developer can begin coding very soon after joining a team, though the initial coding tasks are likely to be simple at first. However, developers need more domain-specific knowledge and experience before they can do some of the other tasks necessary within a software team. It takes a long time for developers to accumulate the knowledge needed to debug production issues, make manual production touches, or scope out complex features. As seniority rises, coding productivity rises too, but the percentage of work time spent on coding typically goes down.

Task distribution by team composition. On teams where everyone is experienced and everyone is roughly equal in skill, the balance of design, coding, devops, and livesite work is likely to be similar between team members. However, teams with many inexperienced developers and high variation in experience level tend to be more specialized. On highly unequal teams, coding work overwhelmingly falls upon junior developers since that’s all they are currently prepared to do, while experience-dependent tasks overwhelmingly fall upon the senior developers since that’s where their experience is needed most. Non-coding time tends to rise with seniority (previous point) but the effect is exacerbated further when a team has a high number of junior developers.

My job is structurally predisposed towards having a low code change frequency: my product (a PAAS cloud API) is low on the stack, it is mature, it is very complicated, it is customer-facing, the fear of introducing regressions is high, and the code check-in gate is demanding. In contrast, the hackathons I have attended in recent years are the exact opposite of my day job: the code is high on the stack, the codebase is small, the product is typically unreleased, things like design and devops are neglected, the check-in gates are lax, I had the coding-heavy workload of a junior engineer, and nearly all the non-coding work was done by the team leader.

So what happened in March 2021? My coding output was already in a long-term decline after peaking during my first 1.5 years on the job. My pull requests got rarer over time but were usually for increasingly complicated code changes. A few months before March 2021, a re-org and some new college hires created a glut of fresh low-tenure developers on my team. There was no shortage of developers on the team who could code, but there was a relative shortage of long-tenured developers who had lots of accumulated domain knowledge. For me, March 2021 consisted mostly of design work and livesite investigations. Many coding tasks got put in the backlog because of me, but for the first month in my career, I was never the one who ended up writing them.